- Home

- Robin Page

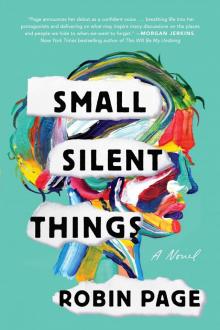

Small Silent Things

Small Silent Things Read online

Dedication

For, my love, John Beran, and also in memory of my brother, Rick Page

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part I

Prologue: Jocelyn

Chapter One: Jocelyn

Chapter Two: Simon

Chapter Three: Jocelyn

Chapter Four: Simon

Chapter Five: Jocelyn

Chapter Six: Simon

Chapter Seven: Jocelyn

Chapter Eight: Simon

Chapter Nine: Jocelyn

Chapter Ten: Simon

Chapter Eleven: Jocelyn

Part II

Chapter Twelve: Claudette

Chapter Thirteen: Jocelyn

Chapter Fourteen: Claudette

Chapter Fifteen: Jocelyn

Chapter Sixteen: Claudette

Chapter Seventeen: Jocelyn

Chapter Eighteen: Simon

Part III

Chapter Nineteen: Jocelyn

Chapter Twenty: Simon

Chapter Twenty-One: Claudette

Chapter Twenty-Two: Simon

Chapter Twenty-Three: Jocelyn

Chapter Twenty-Four: Claudette

Chapter Twenty-Five: Jocelyn

Chapter Twenty-Six: Simon

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Jocelyn

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Claudette

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Simon

Chapter Thirty: Jocelyn

Part IV

Chapter Thirty-One: Jocelyn

Chapter Thirty-Two: Simon

Chapter Thirty-Three: Jocelyn

Chapter Thirty-Four: Jocelyn

Chapter Thirty-Five: Simon

Chapter Thirty-Six: Jocelyn

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Simon

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Jocelyn

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Simon

Chapter Forty: Jocelyn

Chapter Forty-One: Claudette

Chapter Forty-Two: Simon

Acknowledgments

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

About the Author

About the Book

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part I

What is the source of our first suffering? It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak . . . It was born in the moments when we accumulated silent things within us.

—GASTON BACHELARD

Prologue

Jocelyn

AND SO, GLADYS IS DEAD.

Wishes in bunk beds or on the number 17 bus, a prayer at church unanswered. As a girl, she blows out the candles, tries so hard, but in the morning, the menthol Newports are still burning. Her sister, Ycidra, is making breakfast. An extension cord lays limp as a dead snake on a chair back, just waiting to come to life. Jocelyn’s mother is still alive.

Palm a kiss on the roof of a car then, racing through a tunnel, eyes closed tight, hands held—a chain of sister, sister, brother, for good luck: We wish that Gladys was dead. But nothing.

And now, all these years later (and yet all of a sudden), she is dead—her head in an oven, the inevitable snore. The policeman speaks of minutes too late, of next of kin, of only she.

“I see,” Jocelyn says, and grief, surprising and heavy, fills her.

“It happened,” the policeman says, “just this morning.”

Jocelyn is silent, picturing the scene. Even from the coast of California, after more than twenty years, it comes clear: the Winton Terrace government housing, the mustard-colored stove, mice feces in the cereal cupboards. Cirrhosis makes the stomach bloat.

“Are you there?” the policeman’s voice asks, coming through the receiver, but how to answer that?

She places the phone down. She walks into her vast living room. She sits and runs a flat hand along the white suede of the couch. She tells the girl she is, to begin now, to see the death for what it is: clemency, light. She speaks her sister’s name and then her brother’s. The names of the dead like a prayer for strength. Begin, she says. It is safe to begin.

She looks at the ocean from her living room, wonders as she often does, How did I get here, from there? How can I fit in a place like this?

When her husband comes into the room, he asks her what is wrong. My mother is dead, she wants to say, but she is unable to speak. It’s something I’ve always wanted.

HER MOTHER’S DEATH DOES NOT CAPSIZE HER. INSTEAD, IT CREATES A subtle seeping. She is like a rowboat with a tiny hole. She is able to get dressed most days, to make herself clean, but an opening, no matter how small, lets things in. There are glimpses, blurred pictures of history, images she does not want to see, hasn’t seen in such a long time. The death is not the thing, but instead the narrow window.

Her husband catches her taking a toothbrush to the minute stains in the Waterworks tile of their brand-new bathroom. While he is away at work, she hires men to paint freshly painted walls. He notices. He worries. He tells her it can’t happen again. She has to keep it together. We have a child now, he reminds her. Lucy.

“Yes,” she says. “I’m okay.” But a sound, her child voice, a beg, fills a slit. She tries to shake it away.

“Do you want to go to the funeral?” he asks her. “Will that make it better?”

She stands beside him blinking. The visions that abide around her mother’s casket are not good. They are unruly. They are fingers in decomposing flesh, a body lifted out of the earth and stomped on.

“No,” she says. “No.”

At school drop-off, her daughter, Lucy, stares at her as she cries, as if she is some strange creature on exhibition, a fetus in the murky waters of a pickling jar. Jocelyn’s face is hot with tears. She avoids her friend Maud. She has a headache from not sleeping. When the car comes to a complete stop, Lucy undoes her seat belt and hops out of her booster seat. She reaches into the front seat and retrieves a tissue from the luxury car’s glove box. She blots both of Jocelyn’s eyes gently. She is a little adult, ministering to her, although only six years old.

Lucy turns to get her unicorn backpack from the car’s back seat, and then kisses Jocelyn’s cheek.

“Don’t be sad, Mama. Papa says everything always gets better. Why are you sad?”

“I don’t know,” Jocelyn says, because she doesn’t. Gladys dead is a good thing. She reaches back to hold her lovely daughter. “It is something I’ve wanted for a long time, but now I just feel sad about it.” She does not say, It is making me remember. It is making me hear her again.

“Would you like my Goo Bear?” Lucy asks, pointing to a bedraggled-looking stuffed polar bear that she has managed to strap into the seat beside her. “He’ll be lonely today without me, Mama. He’ll help.”

Lucy hands the bear to Jocelyn.

“Thank you,” Jocelyn says, and runs her fingers through her daughter’s wonderful hair, making it neat. “I’ll pick you up, sweetheart. I would never forget you. Don’t you worry. I’ll do better.”

Lucy giggles. “I’m not worried, Mama. Worried about what?”

Chapter One

Jocelyn

1

SHE REMEMBERS HER PAJAMAS. YELLOW WITH THE FEET CUT OUT. HER family was poor. They were all poor. She didn’t know how poor at the time, but she knows it now when she sees her daughter’s pajamas. The feet are intact. The pajamas are stacked high in Lucy’s walk-in closet.

“We’ll just cut them out then,” Gladys would say. “They’ll last ya another year.”

She tries not to think about it. The voices. The cold floors. His leather shoes. Sometimes she worries that she might not be remembering correctly. Her memory isn’t exactly complete. It’s as if the girl she used to be is really a different girl with separate memories. She

remembers, for example, taking a boy’s virginity, but not his name. She remembers having sex with an ecstasy dealer, but not what he looked like. Is that something normal people forget?

It was a small room. She knows her own responsibility. She hasn’t forgotten that.

“I am a criminal,” she says to the therapist—a Dr. Bruce.

Her husband, Conrad, has made the appointment. Your mother is dead, he reminds her, you have to deal with this, a fishhook snagging her back to the past. And inside, she wonders, Will he be arrested if she tells the therapist? Is there a legal obligation? Is there a statute of limitations? He is an old man now, but something in her is still afraid to put him in jail.

“I should have said something,” she says.

“Maybe,” the therapist says.

“I should have done something,” she repeats, adamant.

Her whole body is erect with rage on the plush couch. There is a kind of peace in the hatred she feels for herself.

“You shouldn’t have been put in the position,” the therapist says. “You were a child.”

There is a shift in the room like the movement of clouds. The sudden silence is a presence she can feel. She is stunned. It is as if someone has slapped her flat and hard across the face. Without meaning to, she begins to weep. She is afraid that she will not be able to stop in time to pick Lucy up from school. You shouldn’t have been put in the position. The thought has never crossed her mind.

“I can prescribe something,” the therapist says, handing her a box of tissues. “Your mother’s death will take some time to work through.”

“No,” Jocelyn says. She will force the window shut. No drugs. “I don’t believe in antidepressants.”

“It’s going to get worse before it gets better. You’ll have to do something. Do you exercise? Do you run? Yoga’s good. Church?”

Yoga. Running. She can’t imagine it. Church is laughable. When I was a kid, the minister tried to fuck me, she wants to say, but this woman is such a stranger.

“I used to play tennis,” she says. “I mean before my daughter Lucy was born.”

The therapist writes something in her book. “Why not go back to it? Just try it. You need an outlet, a healthy one. You’ll have to come back here once a week, maybe more. Do you understand?”

“I do,” Jocelyn says, wiping away her tears. You must go, her husband says. You cannot fall apart. Lucy.

“Call me if you need to talk.” The therapist looks at the clock.

Jocelyn stands up, goes to the door. She tries to open it, but it is locked. Panic moves through her. She pulls and pulls on the doorknob. She is in her childhood closet again. The lock clicks, a smoky coat with shoulder pads, the floor that smells like cat pee. The starved cat. All life a thin reed. Her mother had gold platform shoes.

The therapist touches her shoulder gently, unlocks the door, quieting her. “It’s to keep us safe,” she says. “I don’t want anyone coming in here.”

“Keep the crazies out,” Jocelyn says, forcing a smile.

“Exactly.”

2

FROM AFAR THEY LOOK LIKE TEENAGERS, NOT WOMEN IN THEIR FORTIES—firm breasts, tight tank tops, short skirts that are as white as wedding cake icing. The tennis shoes they wear are rainbow colored, grape purple, fuchsia pink, lime green. The colors are emphatic against the private school’s lush lawn. Many of them have high blonde ponytails. Six-year-olds play tag at their feet, and nannies chase them. The mothers in their new outfits look on. Lucy drops Jocelyn’s hand and runs to play with her school friends.

Jocelyn feels relieved when she sees Maud standing just at the front fountain. She is among the group of women. She is stylish in a navy-blue lace shirt with a matching pleated skirt. Jocelyn is grateful to Maud for inviting her to play with them. She compares herself with Maud briefly, because women do that. She knows that she is pretty and being pretty always helps. It is a way to get things, to make friends, a family. But as she moves closer to the crowd of women in front of her, she sees that she has never had this level of competition. Every woman is like a model out of an ad. White, tall, slim. She is not tall. She is not white. She is black, but not obviously so. Where are you from? people ask her, meaning, What color are you? Even other black women aren’t always sure. Maud is the only other brunette besides her.

“Jocelyn!” Maud shrieks when she sees her, excitement in her voice. “You look great. You look fantastic. God, I’m so glad you’re coming.”

Jocelyn smiles. Forces a confident expression, hugs Maud. She looks intently for Lucy. I have to keep an eye, she thinks. I will protect you.

“Let me introduce you,” Maud says, and then the introductions, all around.

The faces are older up close. Lines present. Unlifted jowls. Botoxed foreheads unmoving.

The women seem nice, but she can tell they are sizing her up: How old is she? Has she had work done? What about her clothes?

“Let’s get the kids into school and then carpool,” Maud says. “I’ll tell Kate that we’re partners. I mean just to begin with, so you won’t be nervous.”

Jocelyn has had her hair straightened, her racquet restrung. A new bag from Stella McCartney for her gear. She decides to be all in. Maud is so nice.

“I’m not nervous,” she says, smiling her best smile. She is very nervous. “I’m ready to kick butt.”

The women like this and titter.

“You’ll love our coach,” Erica says, looking her up and down.

“I bet,” Jocelyn says. “She seemed really nice on the phone.”

“Live Ball,” Theresa says. “It’s the best.”

3

LIVE BALL GOES VERY WELL, ALTHOUGH TENNIS ISN’T EXACTLY LIKE RIDING a bicycle. She is okay, but out of practice. The pro welcomes her with feeds that are easier. They have a higher bounce. It’s discreet. Jocelyn knows enough to make sure to put some good shots away, to move a few of the women around. Being in a group of women is always about subtle power.

She isn’t the best there, but she isn’t the worst either. Some of the women seem already to be vying to partner with her, assessing her skills, asking her availability. The coach is excellent. Her name is Kate. She is a blonde beauty with green eyes. Jocelyn tries not to stare.

When it is over, Jocelyn bends from the waist to pick up her bag. She feels infinitely flexible. She is aware of her skirt, the length, just cresting below her rear, how young she feels after the drill, how alive. Nothing negative enters her brain: not Gladys dying, not Winton Terrace. There is just the black sheen of an unlit window.

“Let’s get lunch,” Maud says. “You were great.”

“Let’s,” Jocelyn says.

They have reached the gate when the coach calls to her. She turns. Kate is smiling—white, wonderful teeth. The blonde hair is in a braided bun. It is as thick as a man’s fist. “You’re a lot better than you said you were on the phone,” she says.

Jocelyn feels herself blushing. “Thanks,” she says.

“Are you coming back again?” the coach asks. “Did you have a good time?”

Jocelyn feels as if she is being asked on a date.

“She’ll be back,” Maud says. “Don’t worry.”

“I wasn’t worried,” Kate says, and a little thrill goes down Jocelyn’s spine.

Chapter Two

Simon

1

HE IS IN HIS NEW PENTHOUSE CONDO BY THE SEA. BUT AT FIRST, UPON waking, he does not know this. There is the pygmy, as there always is—his image. Simon knows he is not real. A squat black body. His penis much larger than Simon would have guessed. Hutu, Tutsi, Twa—these are the ethnic categories to fit into. There is his dead wife too. Vestine. Serious Vestine. My one, he thinks. My only.

He knows better than to stand too quickly. He is used to this—the hallucinations, the living dreams—all consequences of trauma. He is usually not unnerved by it, but today something is different, some element is off. There is a voice in the room today, a new one, and because he

cannot locate it, he is alarmed by it. He reaches up to tap his pocket, trying to ground himself. The letter is there.

Papa? Papa? the voice says, and he thinks in a dizzying way, Could it be her come to see me? Impossible, he reminds himself. “She is gone,” he says out loud. The muddy swamp is gone. The terraced mountain down which they fled is gone too. He is the thing left.

He sits up when the voice calls Papa again, because suddenly he is certain it is her. It must be her. Who else would call him Papa?

The room is dark except the sun-lit edge of the shade. It is difficult to see, but he is trying. He has to locate the source of the voice: Papa, Papa, now more like a song. Less determined, dreamy even. He waits. So still. Be still, they said to her, but how do you keep a child still? He blinks, searching.

He is almost over his grogginess, almost stabilized. Focusing on the small things in the room helps. He can tell now that the voice is not in the room at all, but instead is coming from the exterior hallway. But could she be? Is it because of the letter? Too old to say Papa, and of course not possible, but possible. Not likely though. Would she come without invitation? It is because of the letter, but that doesn’t make sense. He has not answered her yet.

He does not stand up, but stays, sitting on the edge of the bed, waiting and listening. His feet are like two heavy weights on the floor. The trembling starts. He closes his eyes. Covers them with his large hands. His thighs shake as a woman’s thighs do after childbirth. Not a woman’s, the memory says—Vestine.

He can hear little feet now. A scampering. She had remained on the toilet, her teeth chattering, her legs moving up and down at a blistering pace. It was his job to hold the baby. He nuzzled her small round head. She was in a pink onesie, the diaper the size of his right hand. He had taken pictures of her ugly little feet. Claudette, they called her, after a favorite auntie.

He stands quickly, an electric shock of remembrance lifting him off of the bed—frantic glee at the memory. Could she be? How, though? For a moment, it is wonder, possibility, not fear. If the pygmy is here, some part of him concludes, why can’t she be?

Small Silent Things

Small Silent Things